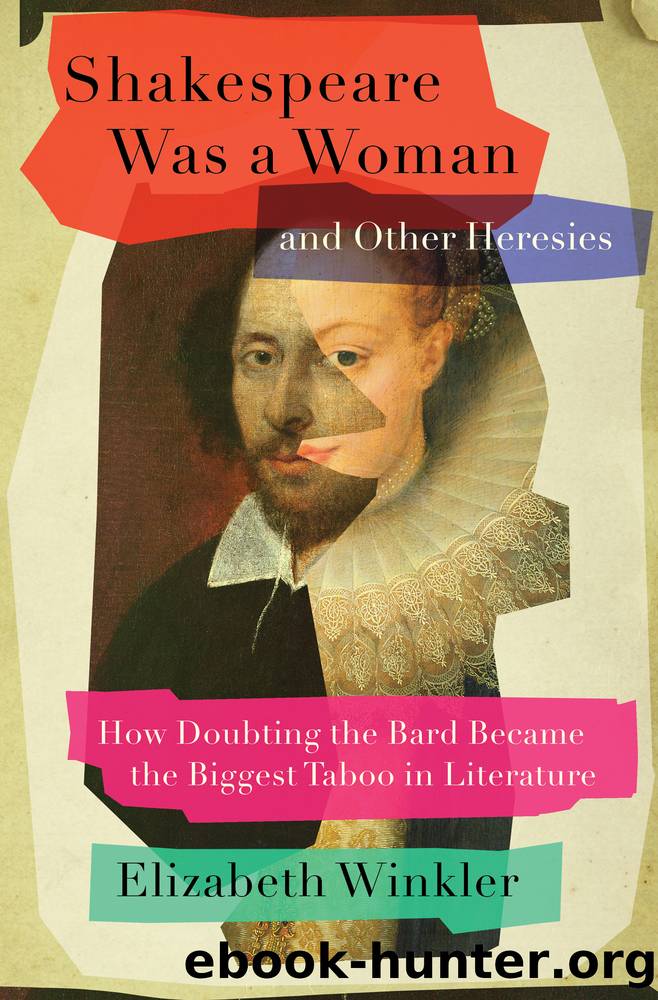

Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature by Elizabeth Winkler

Author:Elizabeth Winkler

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Published: 2023-05-09T00:00:00+00:00

* * *

Except, of course, that it hadnât. Shakespeare scholars were no more willing to accept the Oxfordian heresy than they had been to accept the Baconian one. Looneyâs book was âa sad waste of print and paper,â Alfred Pollard wrote in the Times Literary Supplement in March 1920, setting the tone for the academic dismissal of the Oxfordian theory. âAlmost any manâs life could be illustrated from Shakespeareâs plays,â insisted Pollard, a professor at the University of London. (If that is so, Looney responded in a letter, please explain why âit has been impossible to do anything of the kind for either William Shakespere or Francis Bacon.â) Critics made the predictable jibes about Looneyâs surname (What a looney!), attacked skeptics as snobs, dismissed the biographical parallels to Oxfordâs life as mere coincidences, and maintained that Shakespeareâs works were the product of his miraculous imagination.

Their main argument was that Oxfordâs death in 1604 ruled out his authorship, based on the assumption that the plays were written between roughly 1590 and 1612. But the dating was originally suggested to fit the life span of the man from Stratford. As the scholar E. K. Chambers wrote, it is âa hypothesis which⦠is consistent with itself and with the known events of Shakespeareâs external life.â No one knows exactly when the plays were written, only when they were published and sometimes when they were performed. Scholars disagree among themselves about dates of composition. Sidney Lee gave Allâs Well That Ends Well a composition date of 1595; others placed it earlier, around 1590â92, and still others as late as 1602âa twelve-year span. Scholars see jokes about âequivocationâ in Macbeth as a reference to a series of trials in 1606, which rules out Oxford, but the term equivocation was already in use in trials in 1581 and 1595. As Nicholas Brooke, who edited the Oxford University Press edition of Macbeth, writes, âThere is no evidence to contradict 1606, but there is also very little to support it.â The Tempest, which features a shipwreck on an island, is dated to 1610â11 based on a 1609 letter describing a real-life shipwreck on the island of Bermuda. But there were many accounts of shipwrecks that could have inspired the playâand the 1609 letter wasnât published until 1625 anyway, making it an unlikely source. (Oxfordians argue that the play was more likely based on Decades of the New World, a series of reports published in 1511 about voyages to the Americas.) If scholars donât know exactly when the plays were written, how can they be certain Oxfordâs death ruled him out?

Coverage of Looneyâs book was wildly uneven. While English professors trashed it, reviewers outside of academia praised it. âThis is a remarkable book,â the Bookman Journal reported. âIt is to be hoped that those who have preconceived opinions will attempt to put them aside and judge the work without prejudice.â The Halifax Evening Courier wrote that Looney âmakes a far stronger case for Oxford than has ever been made out for Bacon.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| ASVAB | GED |

| GRE | NCLEX |

| PRAXIS | SAT |

| See more | Flash Cards |

| Study Guides | Study Skills |

| Workbooks |

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13339)

The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy(8918)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8359)

Wonder by R. J. Palacio(8095)

The Lover by Duras Marguerite(7887)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7805)

The Circle by Dave Eggers(7098)

Deep Work by Cal Newport(7054)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6920)

To All the Boys I've Loved Before by Jenny Han(5833)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5762)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5070)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4509)

1,001 ASVAB Practice Questions For Dummies by Powers Rod(4493)

Cracking the GRE Premium Edition with 6 Practice Tests, 2015 (Graduate School Test Preparation) by Princeton Review(4270)

Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade by Robert Cialdini(4208)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(4137)

ACT Math For Dummies by Zegarelli Mark(4039)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4014)